I’ve talked quite a bit recently about metaphysical foundations (particularly in their relation to mystical experiences and whether or not Wyoming exists). Still, I’d like to return to the subject of metaphysics to deal with something a little closer to home for most people: Personality (which is a particular hobby of mine).

You see, our metaphysical understanding of the world colors everything that we perceive and think. It is as inescapable as the air we breathe. Now, in my previous series, I contrasted the metaphysics of Aristotle and Plato/Plotinus. Those two metaphysical bases lead to vastly different interpretations of mystical experience, and they also lead to vastly different interpretations of how we view ourselves.

Here, let me explain what I mean:

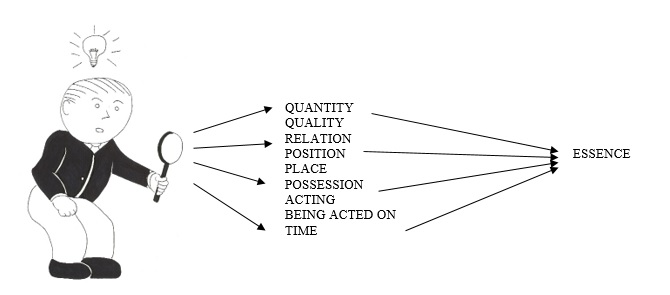

First, let’s recap a bit concerning Aristotle’s approach to the universe. The way to understand the universe for Aristotle is a “simple” process of observation. Then, we take those observations and compile them into a complete picture (i.e., the process of induction). Aristotle believed that he could reach an understanding of the essence (ousia) of things by observing nine other categories of being: quantity, quality, relation, position, place, possession, acting, being acted on, and time.[1] It looks a bit like this –

While we have created extremely sophisticated philosophies and sciences with tremendous variety in recent times, they all spring from the same metaphysical basis and the same assumption: that measuring all of these categories in the sensory world tell us the essence of something – its being, such-ness, is-ness. For instance, I could tell you the chemical and molecular composition of a tree, but is that describing what it really is? The fact that I could even tell you chemical and molecular composition of something as “the” answer to the question of “What is a tree?” shows how deeply embedded Aristotle’s metaphysics are.

Okay, so why does that matter for how we look at ourselves? To answer that question, let’s take a look at a theory of personality that is built on this basis: the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). I will not go into great depth in describing this tool because I have done so previously, and there are many great resources out there that do so.[2] The MBTI is a wonderful tool, but it is often misapplied in how it is used. I read again and again in books and on the Internet where people seek to use the MBTI as a tool of personal and spiritual growth. While it is helpful to see some of your preferences (e.g., “I like to think about how decisions have future consequences.” ; “I always follow the tried and true method”), this tool was originally developed by Katherine Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers to assist people to work more effectively together in offices.[3] While it is based on the theories propounded by Carl Jung in Psychological Types, it is not a psychological instrument per se.

So, let’s stop and think for a moment. Seeing how you and your co-workers think similarly and differently is an immensely practical tool in a work setting, isn’t it? Now, why would we extrapolate from that benefit that the MBTI is telling us something about our essence – that indefinable “center” that makes us who we are?[4]

Because Aristotle’s metaphysics are always providing the basis of our thought process. Essence is really only a name for the aggregate of the outward, tangible qualities and behaviors of our lives stacked together — along with the reasons we explain our behaviors to ourselves and others.

The MBTI, not to mention Aristotle and practically all of modern science, is an immensely helpful tool, but can it tell you about your essence, your spirit, your inner self?

Not really.

You see, as I mentioned in my mystical experience series, Aristotle leans on Plato for all of that spiritual apparatus. Unfortunately, over time, we have become unhinged from a Platonic (and Neo-Platonic) view of the universe. As a result, Aristotle can provide us with startlingly accurate measurements of the vast expanse of interstellar space – just as the MBTI can tell us that we prefer introversion to extroversion or sensing to intuition, but it cannot tell us why that is meaningful or how that connects us to the universe.

Are you interested in adding meaning to your practical usefulness? If so, then come back next week when I’ll talk a little bit about what Plato, Plotinus, and the Enneagram have to do with each other, and what they all have to do with YOU…

[1]Aristotle, Categories and De Interpretatione, tr. and ed. J.L. Ackrill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963), lines 1b25-2a11. See also Hippocrates G. Apostle, Aristotle’s Categories and Propositions (De Interpretatione) (Grinnell IA: The Peripatetic Press, 1980), 2-3.

[2]For instance, see Isabel Briggs Myers, Gifts Differing (Palo Alto CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc., 1980) and Otto Kroeger and Janet M. Thuesen, TypeTalk: The 16 Personality Types that Determine How We Live, Love, and Work (New York: Dell Publishing, 1988)

[3]Myers, Gifts Differing, xiii, 157-174. See also Kroeger and Thuesen, TypeTalk, 7-9, 281-284.

[4]Of course, we could decide to be existentialists and say that there is no indefinable center, but that’s a topic for another day.